- Introduction

- The Big Picture: Why Story Structure Matters

- Linking Plot Elements: Building Narrative Flow

- Common Pitfalls in Story Structure

- Conclusion

- Additional Resources

Introduction

Every great achievement, or great story, results from mastering segments and not wholes. I don’t promise that you’ll have mastered story structure by reading the previous posts talking about each segment, but that if you work on the segments, the whole will reflect your success. When you practice the different elements of story structure, then you can form seamless narratives in each book, chapter, scene, and page you write.

Since the end of March you’ve been learning about the elements of plot. From Inciting Incident to Resolution, we’ve talked about the importance of each part of your story. Each part of your story can be a make or break point for your reader, so it’s worth giving each section of the story your full attention.

Today, we’ll tie everything together. Let’s grab the needle and thread to suture the elements of plot into a whole story.

The Big Picture: Why Story Structure Matters

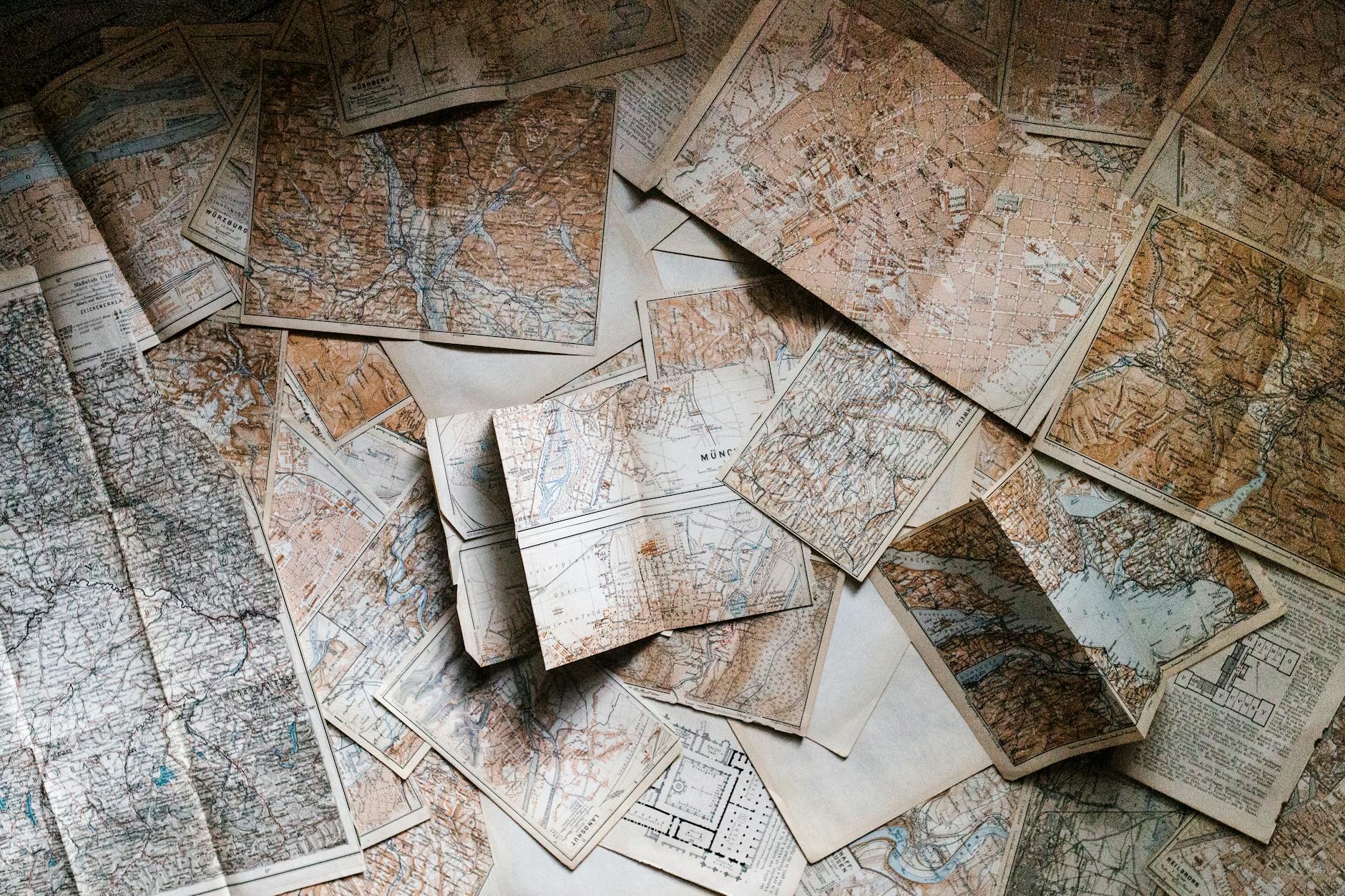

Story structure matters because it creates a map for your readers to follow as they experience your story. There may be concerns that following any story structure will make your story formulaic. This isn’t true. I want you to think of a movie or story where a treasure map was included with the protagonist’s assets. A good map shows different points of conflict, danger, and the path the protagonist should follow. What the map doesn’t show is how each of those obstacles has changed, will be overcome, and what new challenges lay in wait. You give your readers a brief understanding of the map when they read your back cover copy or synopsis.

The ability to translate your story into a logical path shows the readers that you’ve taken the time to provide them a structured story. Readers value purposeful storytelling over meandering detours. Readers aren’t open to side quests that take up three to four chapters like it’s a video game. They have come to your story because something in it caught their attention, or your genre is one of their favorites. The selling point for your book comes from you being able to properly structure your story.

The way you can tell if your structure is working is to evaluate how each element of plot interacts with the other. Each element should build on the previous in a logical sense. Think of the butterfly effect principle. If your protagonist needs to obtain the mystical object to bring peace to the land, then they first must know of the object. Then there must be a reason that they are the ones who can/will obtain the item. The mystical object is most likely protected by something and hidden in a hard to reach area. Before the protagonist obtains the item they’ll need to face a large challenge that truly tests them. Then the protagonist gives their final defining moments in what they do with that mystical object.

If any of those parts don’t seem to line up, say the mystical object is actually just in the protagonists basement and doesn’t challenge them to obtain, then your structure will weaken. This example is a very simplified form, but I hope if gives you an idea of why the story structure is important and it’s impacts on the book.

Linking Plot Elements: Building Narrative Flow

Let’s build on the previous section by building your narrative flow through the elements of plot.

The inciting incident sets up the rising action through a single, key, event that changes the protagonist’s life somehow. Whatever it changes, this influences the type of rising action your character faces in the build-up to the midpoint and on. When the inciting incident is the gaining of a magical ability, then the rising action will encompass all the good and bad things that come along with gaining magical abilities. If they are common, your character will most likely end up at a magic school, if they are uncommon, the society you’ve built will define if they’re on the run or instantly famous. The rising action will teach them the basics of the changes, and set up lessons that should pay off after the midpoint shift.

The midpoint shift will focus your protagonist’s path toward the climax and give them a little more realism in the situations. While still part of the rising action, the time between the midpoint shift and the climax should refine the character, their skills, and their understanding of the change that the inciting incident triggered. The excitement, refinement, and potential downfall will drive the readers to the climax, which should resolve the change created by the inciting incident in some way. For example, in The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, the midpoint shift happens when Katniss Everdeen forms an alliance with Rue, changing her strategy in the Games.

The climax resolves the major conflicts, including but not limited to the conflict introduced during the inciting incident. If you look at the Harry Potter as a series, you’ll see that through the final battle with Voldemort resolves and reinforces the boy who lived and end the Voldemort timeline. The climax couldn’t have happened if Harry had never survived and if Voldemort hadn’t hidden his horcruxes, then he couldn’t have been a threat in Harry’s world. Without the rising action and all the lessons learned from the rising action, Harry, and his friends wouldn’t have been able to save Hogwarts and the wizarding world. Now that your climax has resolved the major conflicts, we close out any other important and unimportant sub-plots to show the direct effects of the climax.

While the falling action and resolution give closure to the story, they also ask the question of what the world would look like if the protagonist hadn’t taken the journey they did. Without the inciting incident, the character might never have changed, or changed in different ways. Imagine if Harry remained stuck in the muggle world and he never got that letter. I have a feeling that would have been a much darker story and created a world of chaotic magic. Next, what events in the rising action remain unresolved, and which of those needs to be resolved before the book ends? Most likely, these will be tied to things the protagonist couldn’t worry about noticing until after the completion of the climax.

By carefully linking these plot elements, you can create a compelling and cohesive narrative that keeps readers engaged from start to finish.

Common Pitfalls in Story Structure

There are a lot of common pitfalls, but I want to address two of them that may benefit you the most as you’re working on your story’s plot.

Sagging Middle

Pitfall: The story loses momentum in the middle, leading to a lack of engagement.

We’ve all heard about it, and it has many titles. Yet, with how much attention is drawn to it, the sagging middle, muddy middle, or whatever you want to call it, is still prevalent in many stories. There’s something about the middle of the journey that like a mid-life crises that drives your story onto strange paths that weren’t supposed to be followed. The story loses its momentum because it feels like there’s a bit of meandering to give you more pages between the inciting incident and the climax. We’ve gotta write at least 200 pages of rising action if you’re planning to write a 400-page book.

Solution: Introduce subplots, character development, and escalating conflicts to maintain interest and build towards the climax.

There’s a lot that has to happen in the middle to prepare the protagonist for the climax. Subplots, character development, and escalating conflicts will do more than maintain reader interest. When laid out properly, your middle can provide hints, critical knowledge, and call-backs to previous chapters that will be important in your climax. This is where the re-readability of your novel comes into play. How many books have you read and then had to re-read because you want to see all the details you missed and how that knowledge changes the story? Give the middle of your story a glance and see what subplots, character development, or escalating conflicts are driving your readers along.

Example: To avoid a sagging middle, consider how J. K. Rowling introduces various subplots and character arcs in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, such as the Triwizard Tournament tasks and the growing tension between characters.

If you’ve found yourself with a sagging middle, it’s okay. Being able to recognize it is the first step in transforming your middle into something memorable.

Rushed Climax

Pitfall: The climax happens too quickly, without sufficient buildup, making it feel unearned.

The early climax can be a sign of many things. Maybe you’re too excited to finish the book, or get to a certain scene. Other times, it may show that you haven’t fully plotted out the second half of your second act. You can tie the latter to the struggle of the muddy middle as mentioned above, or you need to add some scenes and chapters to feel like the climax has been earned. The issue with the rushed climax is it leaves readers feeling unsatisfied even if you have written a fantastic climax.

Solution: Build tension gradually and ensure the climax is the result of the protagonist’s actions and decisions throughout the story.

A lot of this was already addressed in the messy middle section, but lets focus on the climax. If you’ve established what your climax is, it’s time to pull it apart and find the critical elements that drive it. Your Protagonist is going to make their ultimate choice in the climax, so you’ll need to show that they’ve developed the ability/knowledge to make this decision. Then your antagonist will be at the height of their philosophy, seeing the Protagonist as the enemy. You’ll want a scene/chapter to show the antagonists’ philosophy and possibly a chance for the protagonist to join them. Your protagonist will probably have some sort of support system. How do they go about gathering them and why do the allies join them?

Example: “In The Hunger Games, Suzanne Collins builds tension through the escalating dangers Katniss faces, ensuring the climax feels like a natural and satisfying culmination of her journey.”

Conclusion

As we’ve journeyed through the elements of plot and how they work together, remember that story structure isn’t a rigid formula but a dynamic framework that supports your creative vision. By mastering each segment—from inciting incident to resolution—and understanding how they connect, you’ll craft stories that resonate deeply with readers.

The true art of storytelling lies in making these structural elements invisible, allowing readers to be swept away by the narrative rather than noticing the scaffolding. Whether you’re wrestling with a sagging middle or refining your climax, remember that intentional structure creates purposeful storytelling.

Your map is now complete. It’s time to guide your readers through an unforgettable journey.

Additional Resources

- Revisit the Elements of Plot:

- Books

- Save the Cat by Blake Snyder

- The Anatomy of Story by John Truby

Previous Writing Post: Falling Action and Resolution: Bringing It All Together

Next Post: Conflict: The Engine of Your Plot

Discover more from Kenneth W. Myers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Conflict: The Engine of Your Plot – Myers Fiction

Pingback: Myers Fiction May 2025 Newsletter – Myers Fiction