Introduction

There are a handful of story images that readers and viewers alike can recall through generations: Luke Skywalker gazing at the twin suns of Tatooine, Katniss Everdeen volunteering as tribute, and Harry Potter receiving his Hogwarts letter. These iconic moments mark the beginning of legendary hero’s journeys. What makes these stories memorable and resonant? One element might be the legendary story structure that accompanies these legendary heroes.

The Hero’s Journey is often seen as the core structure of any tale of a legendary hero. While it’s come under scrutiny in recent years, it remains a common plot structure used by storytellers across the board. Joseph Campbell believed in a monomyth of the Hero’s Journey and studied ancient tales to identify the key elements that appeared in each. His most famous work, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” set the concept of the Hero’s Journey into a single book that many still reference today.

Understanding how to write a story using the Hero’s Journey is key to crafting your own tales of legendary characters. It also provides elements that are shared across many genres. The great thing about studying structure is that it doesn’t just teach you about that specific story structure; it helps you learn the elements of storytelling through different methods. Each genre has its own requirements, but the plot structure you use can add freshness to books that might otherwise fall into just another “genre” book category. So let’s take a minute to learn more about the history of the Hero’s Journey, and then we’ll dive into it.

Background and Context

As mentioned earlier, the Hero’s Journey began as Joseph Campbell’s theory that all mythic narratives share a fundamental pattern. To clarify, mythic narratives are stories that draw on tropes, themes, and symbolism to create legendary tales that convey a culture’s values and customs. These stories have captivated readers and viewers alike since storytelling began, but Joseph Campbell wasn’t the first to propose such an idea.

Before Joseph Campbell published ‘The Hero With a Thousand Faces’ in 1949, several scholars had proposed similar concepts. Otto Rank, Lord Raglan, and Leo Frobenius laid the groundwork for later theories like Campbell’s. In 1904, Frobenius, a German ethnologist and archaeologist, embarked on 12 expeditions to Africa, exploring prehistoric art and identifying a motif of descent into the underworld that appears in myths from many cultures. Otto Rank, an Austrian psychoanalyst, developed a hero pattern based on the Oedipus legend, suggesting that hero myths are rooted in children’s experiences and imaginations. Lord Raglan furthered these ideas with his 1936 book, ‘The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama,’ identifying 22 common traits shared by heroes across various cultures.

For over a century, the Hero’s Journey has been studied, with origins stretching even further back in time. It remains a cherished structure in today’s novels and movies, finding its purest expression in Young Adult literature. These stories resonate with generations who still believe in grand heroes and the possibility of achieving legendary status. You can find this structure in series like ‘Harry Potter’ by J.K. Rowling, ‘Percy Jackson & the Olympians’ by Rick Riordan, and ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’ by C.S. Lewis. Each of these stories employs the key stages of the Hero’s Journey.

However, the Hero’s Journey is not confined to Young Adult literature. It is also prominent in non-YA stories such as ‘The Hobbit’ by J.R.R. Tolkien and the ‘Star Wars’ saga (the Luke Skywalker storyline). These stories also follow the essential stages of the Hero’s Journey, demonstrating its universal appeal and enduring relevance.

With that, let’s explore the key stages that make up the Hero’s Journey and why we keep coming back to this story structure.

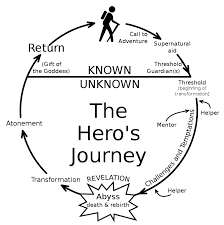

The Three Acts of the Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces offers a great insight into the Hero’s Journey. To delve deeper, Campbell separates the Hero’s Journey into three acts: Departure, Initiation, and Return. As you may recall, we’ve discussed the three-act structure in a previous post. You can use that as a basic outline and enrich it with the Hero’s Journey to add more depth and detail to your story.

Departure

In order to embark on a journey, you must have something to leave behind. The Departure act of the Hero’s Journey is a section of the story that establishes the base, the normal world, often showing the hero in a mental state of stasis. Some of the best heroes are seen in this part of the story as not interested at all in changing anything. As Campbell writes in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, “A blunder—apparently the merest chance—reveals an unsuspected world, and the individual is drawn into a relationship with forces that are not rightly understood.” This quote highlights how an unexpected event can initiate the journey. However, the departure can vary in different stories.

The Ordinary World

As ordinary as it sounds, the normal world doesn’t always mean our world. It’s the normal world of the protagonist. The beauty of Hero’s Journey narratives is that your hero can start as an orphan living on the street or royalty living in a castle. The normal world sets the baseline for readers to understand what they’re living. In J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, the story begins in the Shire, where the hobbits live. Their world is established through interactions, character thoughts, and events occurring at the beginning of the story. This not only introduces readers to the normal world but also the expectations and standards of the people who live there. Hero stories often show how leaving the ordinary world upsets those left behind, and this opposition is often why the hero initially refuses the call to adventure.

The Call to Adventure and the Refusal of the Call

The call to adventure establishes the possible destiny of the hero. This is often administered by the archetype known as the herald. The Herald also serves to signal challenges and changes that the Hero must face to let them know that change is coming. (StoryGrid) There can be the promise of great rewards, a potential “elixir” that fixes whatever the normal world is suffering from, or whatever the hero may see as the answer to their current needs. Now, even when everything sounds good and the promise of gaining the hero’s true desire, the hero will decline the call to adventure on the first or second go. Heroes can be so tied to their current world and current world problems that they can’t see beyond them, or can’t see how they can leave when their “village” without them.

This task, this journey, will challenge them in ways that they may not even realize, but with any change there is risk of danger. The danger of leaving behind what they know to face the unknown. Often the hero’s aren’t walked through the dangers they will face, but their mentor might warn that the journey will be hard. This mentor will prepare and guide them through this journey.

Supernatural Aid (Meeting the Mentor)

When looking into Joseph Campbell’s book, the mentor section is actually titled Supernatural Aid. Mentor is a more modern term that aligns with many of our modern stories. I like the idea of the supernatural aid because it shows that the mentor isn’t always a person. From Merlin to the Fairy Godmother to Athena, mentors can take many forms. Often where the hero’s journey appears in fantasy stories, they hold some kind of magic or power that sets them apart. Though they can just be someone who lived through the experiences before and have the power of knowledge. According to Joseph Campbell’s A Hero with a Thousand Faces, this aid “comes to one who has undertaken his proper adventure.” After this mentor has appeared and the hero has accepted the call to adventure, they’ll reach the first point of no return.

Crossing the First Threshold

“With the personifications of his destiny to guide and aid him, the hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the “threshold guardian” at the entrance to the zone of magnified power.” -Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

The first threshold marks the boundary between the known and unknown world for the hero. This is beautifully illustrated in “The Lord of the Rings” when Samwise Gamgee stops just before the edge of the field and says, “If I take one more step, it’ll be the farthest away from home I’ve ever been.” This literal split in physical location and open pronouncement of the transition might be stated as clearly in your story. Or it could be that once the hero reaches a certain point, they realize the moment everything changed from their normal world to the new world.

The crossing of the first threshold is important because it shows the hero’s willingness to face the unknown and understand that they must prepare for challenges, even if the journey seems an easy one. Joseph Campbell also includes a section called “The Belly of the Whale,” where “The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown, and would appear to have died.” This can be tied to the crossing of the first threshold section and is essentially the moment when the hero realizes they are in the new world and much further from the old than they imagined.

Initiation: The Hero’s Transformation

Now that the hero has left behind their known world, they find themselves in a new and unknown world. This begins the act of initiation, a time for challenges, setbacks, and growth. This part of the story is often the most memorable, as it “has produced a world literature of miraculous tests and ordeals,” as stated in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. As is common with the three-act structure, the Initiation Act takes up a large portion of the Hero’s Journey. With that, let’s look at what takes up so much space.

The Road of Trials: Tests, Allies, and Enemies

“Once having traversed the threshold, the hero moves in a dream landscape of curiously fluid, ambiguous forms, where he must survive a succession of trials.” -Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

In this phase, the hero navigates a world filled with both wonders and horrors. To prepare for their ultimate challenge, they must pass or fail various tests, meet new allies, and identify their enemies. These tests can be literal—challenges of strength, will, or knowledge—or they can be tests of resolve that challenge the hero’s belief system. The growth required throughout this act is as much psychological as it is physical. For example, a hero might face a moral dilemma that forces them to reconsider their values. The initial trials of this phase help the hero realize that they’ll need assistance beyond the Supernatural Aid provided previously.

Allies

Allies play a large part in the Hero’s Journey. The hero will meet people or creatures who reflect aspects of themselves—who they are, who they dislike, who they wish to be, and who they need to be. These may not be obvious at first to the hero, but often, the ones they clash with the most are the ones they need to learn the most from. Allies, or another supernatural aid, can appear in “The Meeting with the Goddess” moment, where the hero gains inspiration or strength for their journey. Another great thing about allies is they can serve multiple purposes. It’s also recommended to round out your side characters with different roles expected in the Hero’s Journey.

You’ve already established the mentor and herald in Act I: Departure, so it’s time to bring in some other archetypes if they aren’t already journeying with your hero. In Act II, you’ll find the shadow, the threshold guardian, the shapeshifter, and the trickster. You can use these as individual characters or turn your allies and enemies into multi-faceted tools.

Enemies

When it comes to enemies, it’s important to remember to scale them. The hero may face the big bad at the beginning of the journey but will fail, or else what would be the purpose of the journey? More likely, you’ll have the hero face enemies that test their different weaknesses just enough to allow them to grow from victory or defeat. Overall, enemies hinder the hero in some way, consuming time, resources, or abilities, making the journey to the final ordeal more challenging. Enemies can even embody “Woman as the Temptress,” challenging the hero’s resolve and commitment to the journey.

The Ordeal

The ordeal focuses on two sections from Campbell’s book, Atonement with the Father and Apotheosis. After your hero has faced trials, enemies, and found some allies, they should be just about ready to take on the ordeal. This is the moment of the story that challenges the protagonist to see if they’ve truly learned and become who they need to be. You’ll often find a Threshold Guardian here. This threshold guardian often involves reconciling with a father figure or powerful authority. The hero must overcome fears, gain wisdom, and achieve a deeper understanding of themselves before they can face the final ordeal. All story events up to that point should act as the final tool that will pull the hero out of their darkest moment before the decision is made to see the journey to the end.

The ordeal, the highlight of the story, and the apotheosis, is the moment where the hero faces the climax of the story. Everything your hero experienced during the story and even before the story began is tested to see what the hero learned from it. It’s an internal battle as much as an external battle. Can the hero forget who they were in the old world and be the person they need to be in the new world? The big bad here often embodies the opposite of the hero, but the hero can understand how that enemy reached the point they have because they have gained the right insights.

The Reward

After successfully facing the ordeal, the hero emerges transformed, often receiving a reward for their bravery and perseverance. This reward, sometimes referred to as the “elixir,” could be the knowledge gained from the journey or reconciliation with the past. Regardless of what the reward is, it should hold value equal to the journey undertaken. Interestingly, the reward could be something as simple as a lover’s bracelet left behind in an abandoned home. The key is how the hero responds to this reward. If they merely say “yes!” and tuck it into their pocket, readers might feel dissatisfied. However, if finding the bracelet brings the entire journey into context for the character and has a profound impact, then the reward is meaningful for both the hero and the reader.

The Return

The Road Back

Now that your hero has achieved their reward, they must decide whether to bring the item, knowledge, or elixir back to their home. It may seem natural to return home with it, as the hero set out on the adventure with this goal. However, that’s not always the case. Joseph Campbell offers an example in The Hero with a Thousand Faces: “Even the Buddha, after his triumph, doubted whether the message of realization could be communicated, and saints are reported to have passed away while in the supernal ecstasy.” In a more modern example, The Giver by Lois Lowry shows Jonas deciding to leave his highly controlled community to seek a life of true emotions and freedom.

Ressurrection

The Resurrection is a climactic moment in the hero’s journey, where the hero faces their most dangerous encounter. This is the most dangerous because it is when the hero is most complacent. They’ve achieved their reward and might think they have an open road for return, having already bested previous challenges. The Resurrection is one last test to see if they’ll hold to everything they’ve learned.

In the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, Orpheus’ final ordeal is to lead Eurydice out of the underworld without looking back—a test of his trust and patience. When he fails and looks back, he loses Eurydice forever.

Sometimes the Resurrection is more literal. In Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling, Harry sacrifices himself to the killing curse. In a liminal space, he has a crucial conversation with Dumbledore, gaining a deeper understanding of his journey, life, and death, and the final steps to defeat Voldemort. Harry’s literal resurrection brings him back with the knowledge to destroy the Dark Lord and bring peace to the wizarding world.

Return with the Elixir

In the final stage, the hero returns to the ordinary world with the elixir—whether it is a treasure, knowledge, or newfound wisdom gained from the adventure. Returning with the elixir has the power to transform the hero’s world. The return to the ordinary world shows the hero as the master of two worlds. The insights gained from the journey help them understand both worlds better than anyone else. They become a source of knowledge and story. The hero will likely be called on another journey soon, but for now, they enjoy the spoils of their journey and try to help their community, making the overall journey worthwhile.

Writing Exercise: The Threshold Guardian Challenge

Let’s keep the practice in our 15 minutes today by focusing on one section of the Hero’s Journey. You’re welcome to work on it as a whole, but try just this segment first.

- Set a timer for 15 minutes.

- Think of an ordinary character in a mundane situation (example: a barista closing up shop, a student waiting for the bus, or an office worker in a meeting).

- In your scene, write about this character encountering their “threshold guardian” – the person, event, or circumstance that marks their departure from their normal world. This could be:

- A mysterious stranger with an urgent message

- An unexpected discovery that changes everything

- A sudden crisis that forces them to act

- A decision point that they can’t avoid

- Focus on three key elements in your writing:

- Show the character’s initial resistance to crossing the threshold

- Describe the physical or emotional barrier between the ordinary world and the unknown

- Reveal what the character stands to lose by accepting the call to adventure

- End your scene at the moment the character must make their choice – will they cross the threshold or not?

This exercise helps you practice creating that crucial turning point in the Hero’s Journey while developing your skills in character motivation, conflict, and scene building.

Conclusion

The Hero’s Journey remains one of storytelling’s most enduring and versatile frameworks. While not every story needs to follow this pattern exactly, understanding these stages provides writers with powerful tools for crafting compelling narratives that resonate with readers. Whether you’re writing fantasy, contemporary fiction, or even non-fiction, the elements of the Hero’s Journey can help you create deeper character arcs, more meaningful conflicts, and satisfying resolutions that stay with readers long after they’ve finished your story.

Additional Resources

Books

- The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell: This is the definitive text on the hero’s journey, exploring the monomyth and its universal patterns.

- The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers by Christopher Vogler: A more accessible guide for writers, offering practical advice on applying the hero’s journey to storytelling.

- The Hero’s Journey: A Map of the Soul by Michael Meade: This book delves into the psychological and spiritual aspects of the hero’s journey.

Videos

- 12 Stages Of The Hero’s Journey – Christopher Vogler Check out this video if you would like an in-depth video to aid your understanding.

- What’s the Hero’s Journey?: Pat Soloman at TEDxRockCreekPark is a great video if you want a quick summary of the hero’s journey, examples, and the so what.

Previous Post: March Newsletter

Previous Writing Post: The Three-Act Structure: A Time-Tested Framework

Next Post: Exploring Alternative Plot Structures: Non-Linear and Experimental

Discover more from Kenneth W. Myers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.